What Are Law Schools Training Students For?

The legal profession and the trillion-dollar global industry are undergoing a transformation. The seminal elements of legal practice—differentiated expertise, experience, skills, and judgment—remain largely unchanged. The delivery of legal services is a different story altogether. New business models, tools, processes, and resources are reconfiguring the industry, providing legal consumers with improved access and elevated customer satisfaction from new delivery sources. Law is entering the age of the consumer and bidding adieu to the guild that enshrined lawyers and the myth of legal exceptionalism. That’s good news for prospective and existing legal consumers.

The news is challenging for law schools, most of whom seem impervious to marketplace changes that are reshaping what it means to be a lawyer and how and for whom they will work. The National Advisory Committee on Institutional Quality and Integrity (NACIQI), a branch of the Department of Education, rebuked the American Bar Association (ABA) in 2016 for its lax law school oversight and poor “student outcomes.” Paul LeBlanc, a NACIQI member, concluded that the ABA was “out of touch with the profession.”

Law schools have made some strides during the past few years-- experiential learning, legal technology, entrepreneurship, legal innovation, and project management courses, are becoming standard fare. A far bigger—and more important step would be for the legal Academy to forge alignment with the marketplace. That would be a “win-win-win” for students, law schools, and legal providers/consumers. Students would be exposed to the “real world” and the skills, opportunities, and direction it is taking. The Academy would acquire context, use-cases, and an understanding of consumer challenges and needs—a strong foundation from which to remodel legal education and training, address the "skills gap," as well as to improve “student outcomes.” Legal providers/consumers would benefit from a talent pool better prepared to provide solutions to the warp-speed pace and complex challenges of business.

What Does It Mean To “Think like A Lawyer” Now?

Law schools have long focused on training students how to “think like a lawyer.” Their curricula were designed to: (1) hone critical thinking; (2) teach doctrinal law using the Socratic method; (3) provide “legal” writing techniques and fluency in the “language of law”; (4) advance oral advocacy and presentation skills; (4) encourage risk-aversion and mistake avoidance; (5) refine issue identification and “what ifs;” and (6) teach legal ethics. Practice skills were usually acquired post-graduation/ licensure by client-subsidized on-the-job-training.

Law schools still teach this way even as the marketplace has changed markedly, particularly during the past decade. Legal delivery is now a three-legged stool supported by legal, business, and technical expertise. Law is no longer solely about lawyers; law firms are not the default provider of legal services; legal practice is no longer synonymous with legal delivery; the legal buy/sell balance of power has shifted from lawyers to legal buyers; lawyers do not control both sides of legal buy/sell; and the function and role of most lawyers is changing as digital transformation has made legal consumers—not lawyers—the arbiters of value. These changes are affecting what it means to “think like a lawyer” and, more importantly, what skills “legal” skills are required in today’s marketplace.

Legal knowledge was long the sole requisite for a legal career; now it is a baseline. “Thinking like a lawyer” today means focusing on client objectives, thinking holistically-not simply "like a lawyer," understanding business, melding legal knowledge with process/project management skills, and having a working knowledge of how technology and data impact the delivery of legal services. Lawyers no longer function in a lawyer-centric environment—now, they routinely collaborate with other legal professionals, paraprofessionals, and machines. Thinking like a lawyer means understanding the client’s business—not simply its “legal” risks. It also means collaborating with others in the legal supply chain, ensuring that the “right” resources are deployed to drive client value, working efficiently, capturing intellectual capital, using data, and advancing client objectives.

Legal performance is shifting from input--hours and origination-- to output-- outcomes and results that drive client value. Lawyers must be attuned to the complexity and speed of business. They must render counsel that considers not only legal risk but also other factors such as brand reputation, regulatory, financial, etc. They must provide multi-dimensional, holistic, timely, and actionable advice. This is what the marketplace construes as “thinking like a lawyer.”

What Should Law Schools Train Students For?

Most law schools continue to train students for traditional practice careers, even as more “legal” work formerly performed exclusively by law firms has been disaggregated and is now increasingly sourced in-house, to law companies, and to “legal” service providers from other disciplines—notably, the Big Four. “Practice” careers are shrinking, and that means that law students and those in the early and mid-stages of their careers must learn new skills to qualify for the jobs that will replace them.

Deloitte projects that 39% of all legal jobs will be automated within a decade. Many of those positions are currently filled by law firm associates who, through labor-intensity (read: high billable hours) and premium rates sustain the traditional partnership model. That model is changing; law firms are hiring fewer newly-minted lawyers and only a small fraction of BigLaw associates make partner. Legal buyers are balking at paying premium rates for non-differentiated “legal” tasks. For many law grads, “gigs” are replacing full-time jobs, and the average lawyer can expect double-digit job changes during her/his career. “Knowing the law” is now a baseline that must be augmented by new skills that are seldom taught by law schools—data analytics, business basics, project management, risk management, and “people skills” to cite a few.

Why are most law schools slow to revamp curricula--even as many have spent tens of millions on new buildings that drive no value to students? And why is the Academy detached from other stakeholders in the legal ecosystem? There are many explanations for the disconnect between the legal Academy’s training and the marketplace’s needs: the ABA’s protectionism of the profession (read: dues-its dues-paying lawyer members); faculty indifference; focus on the profession, not its interplay with the industry; unwillingness to embrace pedagogical change; a narrow, anachronistic, self-serving interpretation of “scholarship,” ranking fixation, a monolithic, undifferentiated approach to legal education/training, and an absence of meaningful performance metrics and accountability. Law schools have begun to pay the price for stasis—declining enrollment, fiscal pressure, migration of talent to other professions/business, and a torrent of negative press. What’s to be done?

Law Schools Should Focus on Consumer Needs and The Skills Required to Satisfy Them

Businesses have different cultures, hiring criteria, target markets, and performance metrics—why not law schools? Most academics would respond, “The goal of business is profit—that’s very different than an educational institution.” Perhaps, but in today’s world, profit is derived from customer satisfaction—a positive experience, a satisfying outcome, and value. Most law schools are receiving failing grades when measured by these criteria. They should, as Mary Juetten suggests in a recent article in the ABA Journal, focus on outcomes. For Ms. Juetten, that includes adding metrics, going beyond substantive law, more practical experience (a/k/a experiential learning), doubling down on dispute resolution mechanisms, and finding solutions for the access to justice crisis by aligning tech products to material marketplace needs (use-case). Let’s hope the ABA takes note of her recommendations.

There is no one-size fits all answer to the training issue, and that’s part of the problem. Law schools have largely undifferentiated curricula and train as if grads from all law schools are preparing for similar careers. That flies in the face of past, present, and future reality. A small band of elite, brand-differentiated law schools (“T-14”—perhaps 20) continue to prepare the bulk of graduates for “practice” careers at similarly brand differentiated law firms, in-house legal departments, law companies, as well as high-level Government, academic, and judicial careers. For the other 170 or so U.S. law schools, it’s a different story—but by no means a bleak one. There is enormous opportunity to train students to better serve law’s “retail” segment. Tens of millions of new legal consumers would enter the market if there were more new, efficient delivery models that better leverage lawyer time utilizing technology, process, data, metrics, and a client-centric business structure. So too are there opportunities for grads of non-elite schools trained in data analytics, project management, knowledge management, and a plethora of other “business of law” positions—many of which have yet to be created.

All law schools should provide grads with: a command of doctrinal law “basics” including legal ethics; critical thinking; people and collaboration skills; business, tech, and data analytics basics; marketplace awareness; a learning-for-life mentality; and an understanding that law is a profession and a business. Law schools must also train students to be client/customer centric. This is far more important than the “lawyer-centric” approach of the past. Students must graduate with a grasp of what legal consumers expect of lawyers; what skills are necessary to satisfy those expectations; and what additional/ongoing training will be necessary to drive client value? A law school diploma is no longer the end of one’s formal education—it is a baseline in a lifelong process. This presents a challenge and opportunity for law schools to be the principal source of that ongoing training.

Conclusion

Law schools must become better aligned with the marketplace. It’s consumers—not lawyers-- that now decide how and when lawyers are deployed. This is a path previously traveled by physicians, accountants, and other professions. Service professions—like businesses--must serve the needs of consumers. Those needs are not static. That’s why law schools cannot remain static and must adapt more fluid curricula to meet the needs of legal consumers, not their own.

Source: What Are Law Schools Training Students For?

4 Steps to Funding an Education

As Americans, we have the freedom to explore opportunities and pursue our goals; the sky is the limit. Our belief in endless possibilities is particularly true when it comes to educating our children. Every generation wants to provide their kids with more years of school and a higher-quality education than they received. That’s because we believe that a good education is necessary for a better life. In fact, on average, a college degree will result in higher earnings. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, an individual with a bachelor’s degree or higher is typically expected to earn 67.7% more than an individual with only a high school degree.

But while the aspiration of providing our children with a better education makes sense, we also have to face reality. One obstacle stands between our goal of educating our children and our ability to achieve it: money.

The education funding puzzle is both challenging and complex. The good news is that, like many puzzles, there is a solution. The bad news is that finding the solution requires focus, time and effort. There isn’t a “one size fits all” solution to achieving this goal. Instead, each family’s solution is unique and reflects their philosophy of education, the reality of their cash flow and a realistic assessment of their financial resources.

Subscribe to Kiplinger’s Personal FinanceBe a smarter, better informed investor.

Save up to 74%

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free E-NewslettersProfit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

To create your solution and achieve your goal, you must do four things: prepare, plan, prioritize and persevere.

PrepareWhile preparation is the key to achieving any financial goal, it is especially true when it comes to college funding.

First, you need to decide whether it would be valuable to work with a financial adviser. You may want to choose an adviser because s/he has the experience and expertise to help you determine the cost of your goals, advise you on how to achieve those goals and help you navigate the investment markets along the way.

Next, with or without an adviser you have to determine how much a child’s education will cost in today’s dollars and how much those costs may increase in the future.

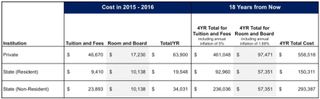

(Image credit: Jan Blakely Holman)

In the chart above, the first column lists the three most common types of four-year educational institutions: private, state (resident) and state (non-resident).

The second column shows annual costs in today’s dollars for each type of school, separated between tuition and fees and room and board. Transportation, books and other fees are not included.

The third column illustrates how those costs may increase if school attendance begins 18 years from now. Because tuition and fee expenses have historically increased at higher average rates than room and board costs, a higher rate of increase has been applied to those costs. (Sources: State school costs, The College Board. Private school costs, Scholarshipworkshop.com. Assumptions: 1.89% core inflation rate applied to annual room and board increases. Tuition and fees are assumed to increase at 5% per year, according to The College Board.)

If you’re like most people, the numbers will surprise you. How much it takes to fund a college education for one or more children can be shocking. But, this is reality.

To make any financial goal more palatable and achievable, you must first determine the entire cost—then reduce the numbers to monthly costs.

Assuming you begin funding your child’s education at birth, you would have to invest the following amounts every month for 21 years (until and through the college years) while earning a 4% average annual rate of return on the dollars you invest:

Swipe to scroll horizontally

Private college: $1,413.06 State (resident): $380.29 State (non-resident): $742.28 PlanNow that you know how much it can cost to fund four years of college, it’s time to create a plan. Begin by asking yourself these questions:

Your answers to these questions will help you decide which approach is most realistic and gives you the best odds of success.

PrioritizeOnce you’ve answered these questions and you’ve managed your expectations, it’s time to prioritize. Today, just as young couples are having children, often they’re still paying off their own student loans. At the same time they’re paying off student loans, their parents are trying to fund their own retirement. Because there are many moving parts, the approach you take and how you prioritize your options requires flexibility and a balancing of various activities.

PersevereYou’ve calculated your goal, and you know what you need to do to achieve it. Now your challenge is to calmly and consciously remain committed to achieving the goal, month after month, year after year. Financial goals are achieved by people who persevere. You want to remain up-to-date and current on education funding laws and options. You want to regularly invest and stay invested through thick and thin despite changes in your life. You want to focus on your goals regardless of the changes, challenges or discouragement you face.

You can solve the education funding puzzle and achieve your goal by preparing, planning, prioritizing and persevering.

Jan Blakeley Holman, CFP, CIMA, ChFC, CDFA, CFS, GFS, is Director of Advisor Education at Thornburg Investment Management, a global investment management firm.

Related ContentDisclaimer

This article was written by and presents the views of our contributing adviser, not the Kiplinger editorial staff. You can check adviser records with the SEC or with FINRA.

Source: 4 Steps to Funding an Education

The Education Factory

Books & the Arts / April 22, 2024

By looking at the labor history of academia, you can see the roots of a crisis in higher education that has been decades in the making.

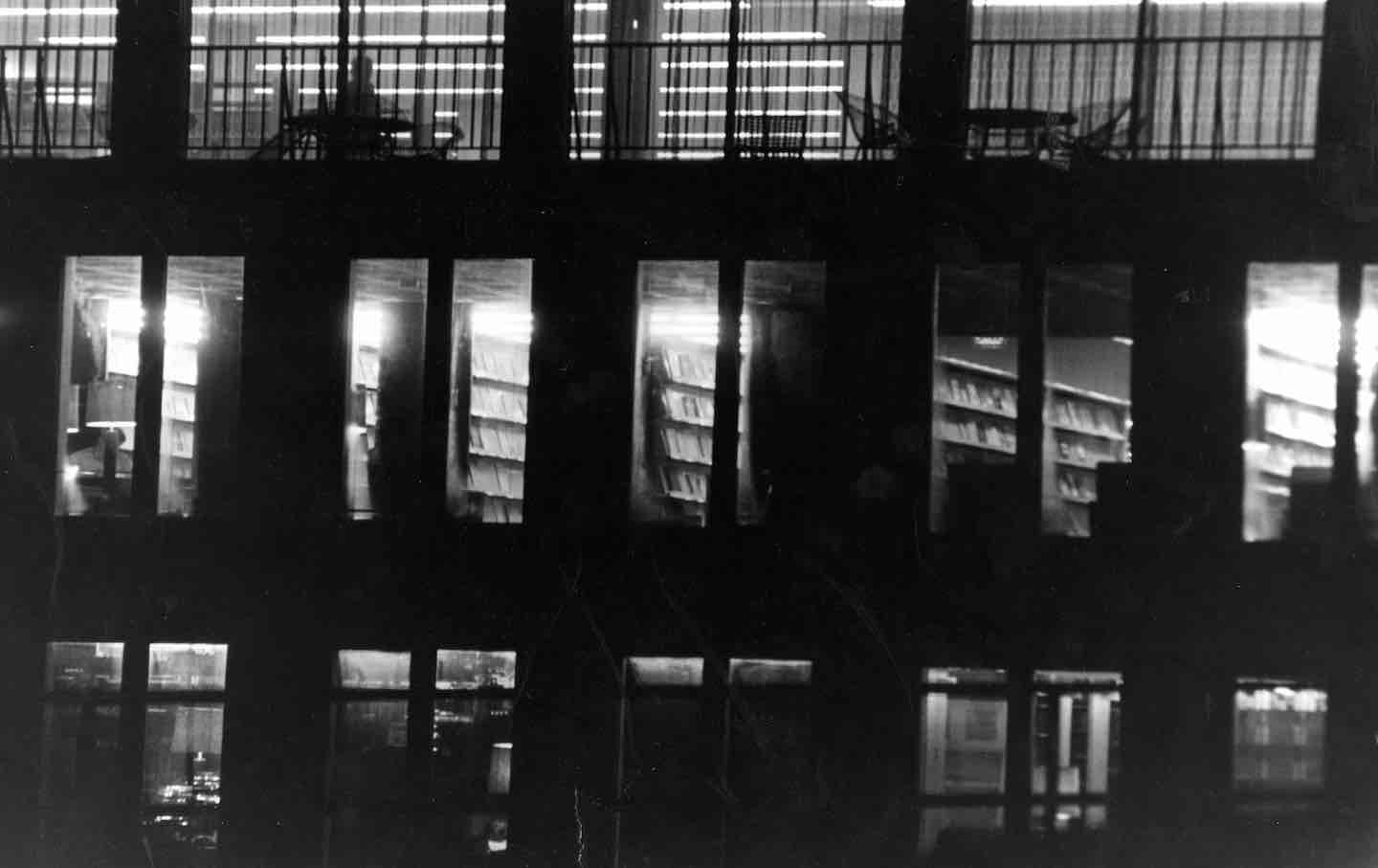

At nighttime, the levels inside the Milton S. Eisenhower Library light up the windows, showing stacks of books and the silhouettes of students working at tables and lounging at chairs, from A Level to B Level and M Level at the top, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, 1965.

(Photo by JHU Sheridan Libraries / Gado / Getty Images)A week before I started my first job as a non-tenure-track contingent faculty member, I found myself in a basement auditorium listening to a university administrator expound upon the transformation of higher education in our century. In an increasingly competitive and fast-paced marketplace, he explained, manufacturers had discovered the need to transition from a “just-in-case” model of production, amassing stockpiles to respond to unexpected surges in consumer demand, to a “just-in-time” model, where sophisticated information technology allowed them to save money on labor and equipment by adjusting output to demand in real time. He paused, letting us ponder what the point of this wonky excursus into business history might be. Then the reveal: The story was about us. Whether a corporation made widgets or forged young professionals, the just-in-time model was the only way of doing business. We used to be able to get away with treating our students’ minds like Fordist warehouses, stuffing them full of knowledge that they might never have cause to use. But times had changed. Now we needed to figure out exactly what the market was demanding they know and teach it to them—no more and no less.

Books in review Contingent Faculty and the Remaking of Higher Education: A Labor History by Eric Fure-Slocum and Claire Goldstene (Editors) Buy this bookTaking this all in, I thought about the first time I came to this campus basement. It was my second year of graduate school at the same university. I’d been invited to a union organizing training, which took place in the room next to the auditorium where I was now sitting for new faculty orientation. The previous fall, the nascent grad student union had narrowly lost an election with the National Labor Relations Board, a result the union was challenging on legal grounds due to some alleged malfeasance by the university. There were rumors that a decision would be coming soon, and that the most likely outcome would be a new election. I’d done some get-out-the-vote work in my department during the first election, but not much more than that. I was determined that if we got a second chance, I’d do my part. I think a lot of people felt that way, and when the NLRB ordered a second election, we mustered a much stronger showing.

It seemed for a moment that I could hear the voices from that first training echoing through the walls. I wondered if the administrator sermonizing before us might not hear them too, a specter haunting his homily on market discipline. What went unspoken that morning was that many of us sitting there were just-in-time employees, not merely just-in-time educators. We were hired on a short-term basis, ostensibly to fill short-term needs (even though many contingent faculty members teach introductory or mandatory courses that must be taught each year). We didn’t know, in many cases, if we’d still have our job in a year’s time. We all knew, however, that without a doubt we’d be laid off (“nonrenewed”) at some point, regardless of our performance, because of the university’s insistence on capping the length of time that individuals were allowed to hold most non-tenure-track faculty appointments. The university had no desire to accrue any stockpiles.

This system, as the labor scholars Eric Fure-Slocum and Claire Goldstene show in their new volume Contingent Faculty and the Remaking of Higher Education, is hurtling headlong into crisis. Contingent faculty have no choice but to discover how to wield the power in our ever-increasing numbers. By one estimate, close to three-quarters of teaching staff in US colleges and universities are now employed on a contingent basis—on one-year, one-semester, or even one-course contracts, often working “part-time,” without benefits, toiling at multiple institutions simultaneously in order to afford rent. In the 1970s, about three-quarters of postsecondary teachers worked on the tenure track, and a greater proportion of contingent instructors had full-time professional employment and taught for supplemental income or for the intrinsic rewards of teaching. The professoriate was proletarianized in the span of a generation. It was an explosion of precarity and exploitation. And now the fallout is here: a battle between the corporate university and the contingent faculty majority for the future of higher education.

What happened? The explanation I hear most often, on those occasions when the taboo against open discussion of “adjunctification” is breached, is budget shortfalls: Universities today, the story goes, just can’t afford to spend as lavishly on faculty as they once did. This excuse often originates in the university’s administrative C-suite (among deans, provosts, and the presidents) and then is propagated dutifully down the ranks, sometimes accompanied by half-hearted lectures on neoliberalism and the Long Downturn and the end of the Cold War university. The essays in the first part of Contingent Faculty and the Remaking of Higher Education obliterate this mythology. Sue Doe and Steven Shulman, scholars at Colorado State University, present especially revelatory data. Rather than being imposed on administrators by revenue shortfalls, Doe and Shulman show, faculty casualization is driven by the quest to maximize what they call “instructional surplus,” the amount of money a school rakes in from each student minus what they spend to educate them. The schools that rely most heavily on contingent faculty are not those that are struggling to afford to educate students (such schools are few and far between, Doe and Shulman find) but those that are banking the most money per student. Adjunctification, then, is the byproduct of a financial equation: a tool to wedge open the divide between how much a school spends on education and how much it earns per student in tuition, fees, and government subsidies. American higher education demolished the tenure track not in order to make ends meet but in order to amass profits. (Explicitly for-profit schools, as Doe and Shulman observe, have all-contingent faculties.)

The question of faculty casualization, in short, is the question of how American colleges and universities transformed into profit-hungry corporations masquerading as educational nonprofits. Part of the answer, as the historian Elizabeth Tandy Shermer argues in her contribution to the collection, is that this transformation really represents a reversion to the historical norm after a brief and decidedly incomplete mid-20th-century interruption. When postsecondary schools were built, in the 18th and 19th centuries, they relied on land and wealth extracted through slavery and Indigenous genocide; Gilded Age robber barons transformed universities into R&D labs and workforce training centers. Faculty labor organizing, inspired by New Deal–era union activism, ultimately forced schools to improve job security and working conditions, including by implementing the modern tenure system—but the “golden age” was always an uneasy compromise.

The collapse of this compromise occurred gradually and at first imperceptibly. There was no epochal shift in administrative consciousness, just a series of smaller dislocations that changed the calculus about the rationality of the tenure settlement. Changes in the funding landscape did play a role here, as a variety of contributors show. Reductions in government expenditures prompted by stagflation in the 1970s fostered a cost-cutting sensibility across higher education. An increasingly “nontraditional” student body, enrolled part-time or as their personal finances would permit, created unpredictable fluctuations in tuition revenues that also prompted austerity. The expansion of the student loan industry allowed schools to jack up tuition prices, but the consequence was a competition to prove to prospective customers that the “student experience” was worth their investment—hence the drive to maximize profits that could be diverted to fund state-of-the-art dorms, gyms, stadiums, and other campus amenities.

The essays in Contingent Faculty and the Remaking of Higher Education also underscore the fact that the more diverse scholars who entered the professoriate in increasing numbers in the late 20th century were, politically speaking, easier to exploit than their predominantly rich-white-man predecessors. Women and people of color were often the first faculty members to find their positions casualized, and they remain disproportionately represented in the adjunct ranks today.

Not only did adjunctification allow schools to cut costs at the expense of their most disempowered teachers, but it also helped higher education weather the campus radicalism of the 1960s and early 1970s, as the scholars and labor activists Joe Berry and Helena Worthen illustrate. Precarious workers are easier to discipline and to discharge. When student demands prompted schools to create new programs in ethnic studies, gender studies, and labor studies, administrations decided to staff these institutions—magnets for subversive types—overwhelmingly with contingent faculty.

Despite their precarity, however, contingent faculty are turning out to be less docile than administrators might have hoped. Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose, and as Contingent Faculty and the Remaking of Higher Education shows, that’s where many proletarianized academics find themselves. There are the daily humiliations: course materials stored in car trunks, office hours held at a local Starbucks, 14-hour days stuffed full of “part-time” teaching, the metastasizing credit card debt. There is the inability to plan one’s life, the ceaseless uprooting and peregrination. The absence of time: to research, to write, to keep one’s courses up to date. The professional insults, the slights both thoughtless and deliberate, exclusion from whatever modicum of faculty governance today’s schools still retain. Above all, the worry: ineradicable, asphyxiating.

So it’s no wonder that contingent faculty and other academic workers are fighting back. The Coalition of Contingent Academic Labor was founded in 1996 to coordinate contingent labor activism across North America; the New Faculty Majority followed in 2009, and Higher Ed Labor United in 2021. Big unions like the Service Employees International Union, the United Auto Workers, and the American Federation of Teachers have augmented the efforts of these coalitions with organizing on campuses around the country, in both the private and public sectors. Academic workers, especially graduate students, have been winning union elections at a remarkable clip lately, frequently recording margins of victory well over 90 percent. In the worst depths of the pandemic, as a variety of contributors document, unions played an indispensable role in combating layoffs and fought to secure safe working conditions.

In a sign of the times, The Chronicle of Higher Education now sells a report titled “The Unionized Campus” that administrators can purchase to learn “how to coexist with academic labor unions.” Some of them, it seems, are listening. The same university that ran such a vicious anti-union campaign when I was in grad school more or less declined to contest our new union for non-tenure-track faculty and researchers when we undertook an NLRB election earlier this month. I’m sure they suspected that mounting an oppositional campaign wouldn’t be worth the effort, and with 93 percent of voters supporting the union, we proved them right.

Ad PolicyPopular “swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

But it’s still not enough. A series of sobering essays that conclude Contingent Faculty and the Remaking of Higher Education seek to explain why, as the labor historian Trevor Griffey puts it, “faculty labor organizing has so far produced limited and often unsatisfying results for its non-tenure-track members.” The byzantine complexity of American labor law is partly to blame. In the private sector, the status of many academic workers under the Wagner Act is unclear and ruled by the ever-changing whims of the NLRB. The board judged tenure-track faculty to be too managerial to merit union representation in 1980, in NLRB v. Yeshiva University. Graduate students and non-tenure-track faculty, on the other hand, are union-eligible—although there has been much flip-flopping on the question of graduate students over the years, and many of us spent the Trump years praying that his right-wing board wouldn’t move to exclude them once again.

Meanwhile, public-sector labor law varies significantly from state to state. Tenure-track faculty at public schools, unlike their private-sector counterparts, tend to be union-eligible, so there are many unions that include both contingent and tenure-track faculty. Such wall-to-wall faculty unions wield more strike power, but contingent faculty sometimes struggle to ensure that their interests are adequately prioritized. In both the public and the private sectors, tenure-track and senior faculty do not always demonstrate solidarity with their contingent colleagues, and some do worse than that. One of the biggest obstacles to academic labor organizing is the industry’s insidious meritocratic culture, the widespread assumption that people who get trapped teaching off the tenure track are victims of their own intellectual or professional inadequacy. Academics who derive their self-worth from their relatively superior status have a hard time supporting the labor movement’s challenge to professional hierarchy.

In many respects, contingent academics confront the same obstacles that bedevil labor organizing among precarious and casualized workers elsewhere in the economy. The high turnover that comes with short-term contracts can wipe out organizing committees without management having to lift a finger. The threat of retaliation is more palpable for workers who toil without even a pretense of job security. And if you’re constantly driving all over your metro area to four different jobs trying to pay the bills, it’s hard to find the time to devote to building or sustaining a union effort at any given workplace. As the contributors to Contingent Faculty and the Remaking of Higher Education emphasize, the casualization of academic labor is just one manifestation of the same underlying dynamics that have driven the emergence of a “precariat” in nearly every industry. We’re in the same gig-economy boat as everyone else.

Looking back on it, I realize there was a great deal of truth in what that administrator had to say to us that day, on the eve of my own entry into the academic precariat. The old model of academic research and teaching is gone for good. Whatever walls we may have imagined sequestering the academy of the past from the pressures of the “real world” have clearly eroded, if indeed they ever existed in the first place. But if university administrators find themselves ever more closely entangled with capital, restructuring their campuses to serve the just-in-time demands of markets for labor and knowledge, those of us on the front lines of scholarship and education have the opportunity instead to embrace the demands made on us by mass movements for social and economic justice. Devoid of the expectation of professional comfort, we may find ourselves able to listen more closely to the Rilkean message that it is the vocation of labor organizers and intellectuals alike to deliver: You must change your life.

Thank you for reading The Nation!We hope you enjoyed the story you just read. It’s just one of many examples of incisive, deeply-reported journalism we publish—journalism that shifts the needle on important issues, uncovers malfeasance and corruption, and uplifts voices and perspectives that often go unheard in mainstream media. For nearly 160 years, The Nation has spoken truth to power and shone a light on issues that would otherwise be swept under the rug.

In a critical election year as well as a time of media austerity, independent journalism needs your continued support. The best way to do this is with a recurring donation. This month, we are asking readers like you who value truth and democracy to step up and support The Nation with a monthly contribution. We call these monthly donors Sustainers, a small but mighty group of supporters who ensure our team of writers, editors, and fact-checkers have the resources they need to report on breaking news, investigative feature stories that often take weeks or months to report, and much more.

There’s a lot to talk about in the coming months, from the presidential election and Supreme Court battles to the fight for bodily autonomy. We’ll cover all these issues and more, but this is only made possible with support from sustaining donors. Donate today—any amount you can spare each month is appreciated, even just the price of a cup of coffee.

The Nation does not bow to the interests of a corporate owner or advertisers—we answer only to readers like you who make our work possible. Set up a recurring donation today and ensure we can continue to hold the powerful accountable.

Thank you for your generosity.

Erik BakerErik Baker is a historian, an associate editor at The Drift, and an organizer for the Harvard Academic Workers-UAW. His first book, Make Your Own Job: How the Entrepreneurial Work Ethic Exhausted America, is forthcoming from Harvard University Press.

Source: The Education Factory